02 - Public Transport - SM

02 - Public Transport - SM

!

Definitions

Public transport

The definition of public transport (PT) is not unanimous. Differente people categorise as PT different modes of transportation.

Public transport (or public transportation, or pablic transit or mass transit) is a system of transport for passengers by group travel systems available for use by the general public, typically managed on a schedule, operated on established routes and that charge a posted fee for each trip

Examples of PT are:

- Buses

- Trolleybuses

- Trams (or light rail) and passenger trains

- Rapid Transit (metro/subway/underground)

- Ferries

Public transport between cities is dominated by airlines, coaches and intercity rail (or high speed rail).

The definition provided has some limitations:

- "managed on a schedule" and "operated on established routes": this is not always true, especially in the case of Demand Responsive Transit;

- "charge a posted fee for each trip": we now have examples of cities or countries where public transport is free

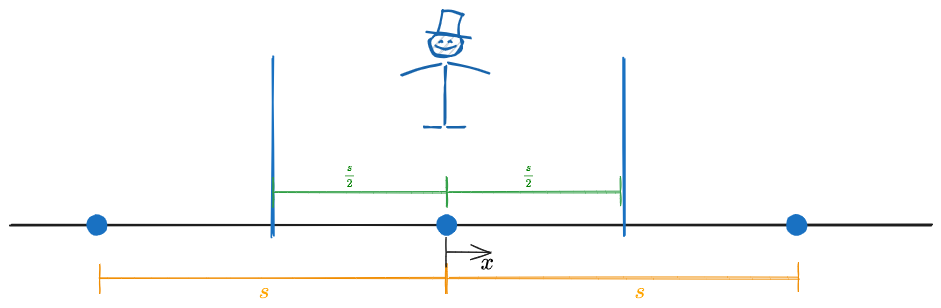

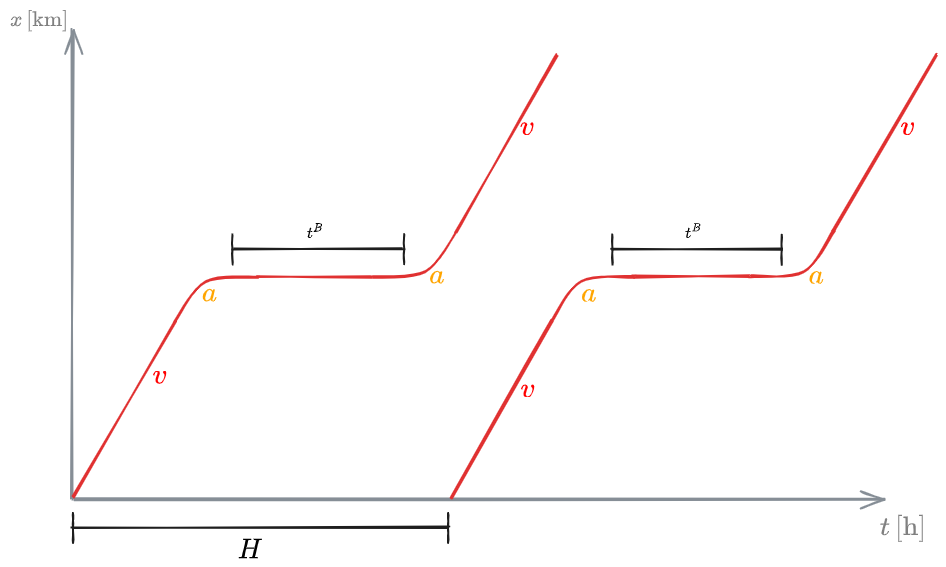

Most PT systems run along fixed routes on a prefixed timetable. More frequent services run to a headway.

In basically every case, using public transport includes using at least one other mean of transportation (walking, driving...).

Public transport can then be classified following different criteria.

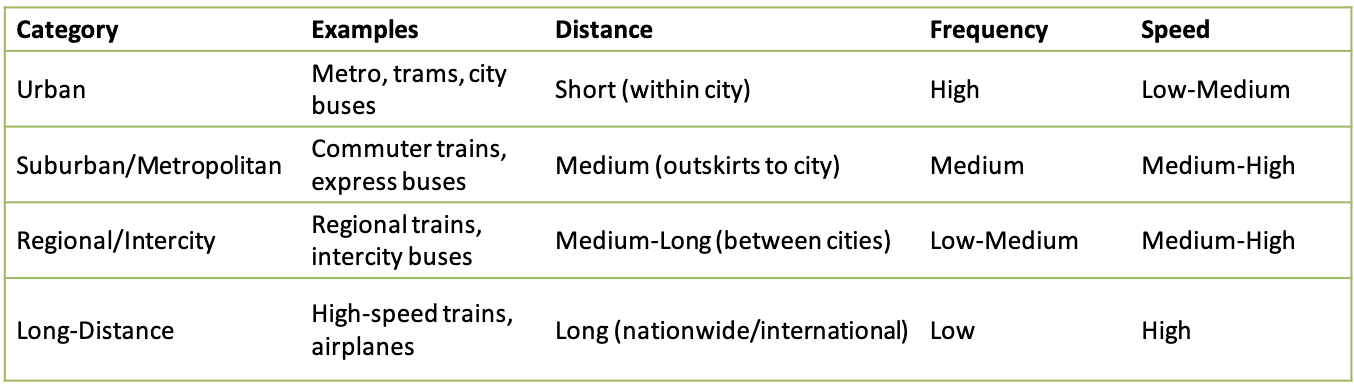

Public transport classification

2 possible classifications of public transport are:

Operation classification

- Schedule based service

- Frequency based service

- Flexible on-demand

Coverage classification

- Urban

- Suburban/metropolitan

- Regional/intercity

- Long-Distance

Public transport route types

- Radial routes

- Circular routes

- Grid routes

- Linear routes

- Feeder routes

- Express routes

- On-demand/flexible routes

Public transport characteristics

PT - Public vs private

Public transport refers to shared transportation services that are available to the general public, typically operated and regulated by the government or public agencies.

On the other end, private transport refers to modes that are owned and used by individuals or specific groups, rather than being open to the general public.

PT - Collective vs individual

Collective transport is a mode where multiple passengers share a vehicle or service, typically following a fixed route and schedule.

Individual transport is a mode where the user has full control over route and schedule, often using a private or exclusive vehicle.

PT - Urban vs Suburban

- Urban transport focuses on high-frequency, short-distance trips within cities

- Non-urban transport connects suburban, regional and intercity areas with longer distance services and lower frequencies

PT - Fixed routes vs flexible on-demand routes

Fixed routes PT operate on predefined routes and schedules, stopping at designated point regardless of passenger demand.

Flexible or on-demand PT adjusts its routes, stops or schedule based on real-time passenger requests.

PT - Dedicated vs shared infrastructure

Dedicated infrastructure is fully reserved for one kind of transport mode: exclusive lanes, . tracks or spaces. They prevent interference with private vehicles

Shared infrasrtcuture can be used by both PT and private vehicles.

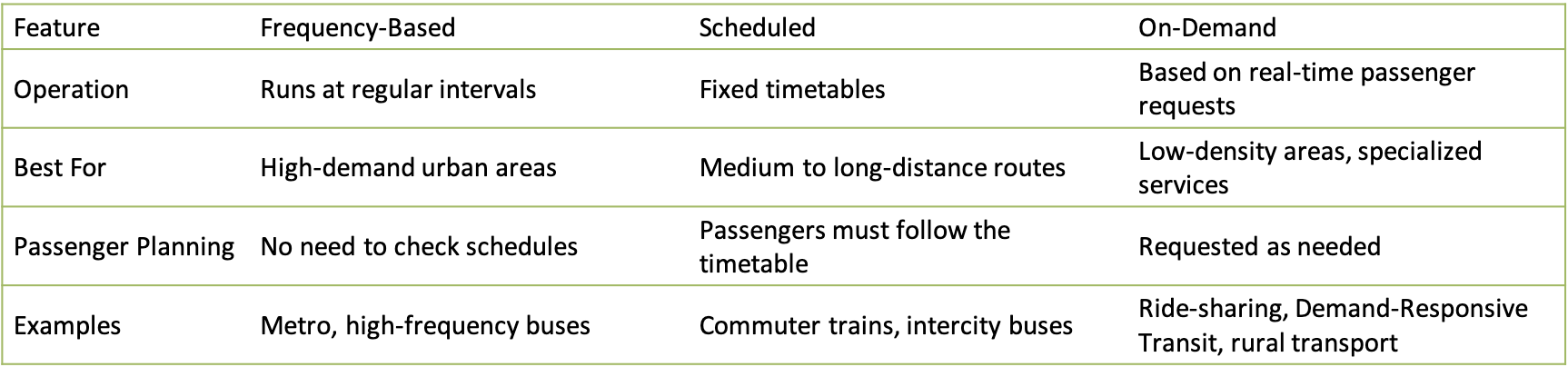

PT - Frequency, scheduled and on-demand

- Frequency based transport is best for high-demand urban areas offering short waiting times and reliability

- Scheduled transport is convenient for long distance services and for commuters, requiring planning

- On-demand transport provides flexibility for low-density areas

PT - Access vs Affordability

Access in PT refers to how easily people can reach and use the transport system. It includes physical, geographic and social factors that determine whether transport is available to all users.

- A dense metro network that covers an entire city

- Bus stops within walking distance of most residencies

- Wheelchair-accassible buses and stations

- Real-time apps and wayfinding for better passenger navigation

Affordability refers to how much passengers have to pay for using transport relative to their

income.

- Subsidized metro fares in major cities

- Discounted transport for students, seniors and disabled people

- Free public transport policies

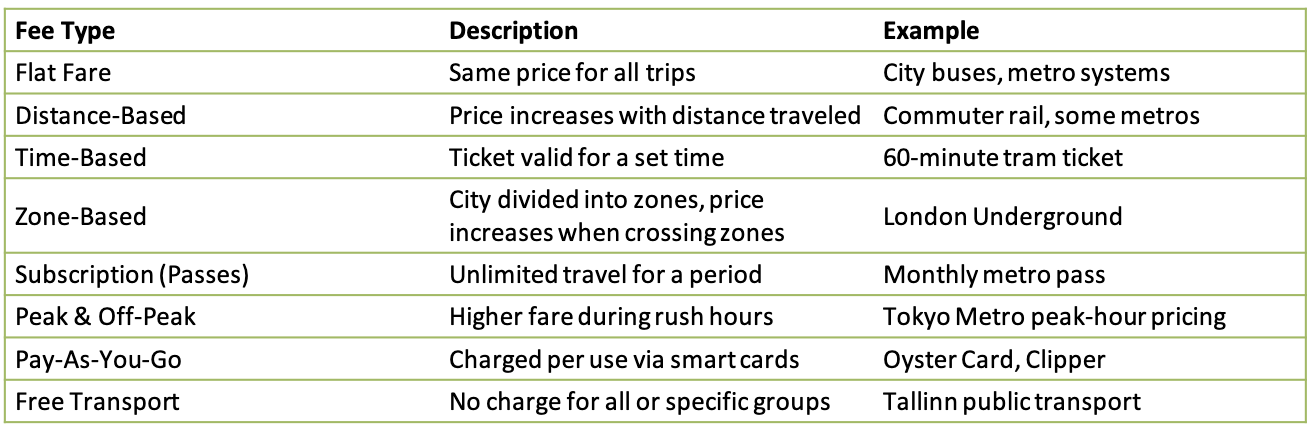

PT - Types of fares

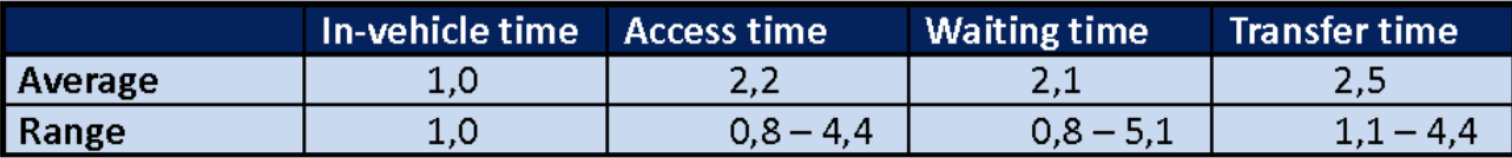

Public transport generalised cost

PT operations make up for a big part of the cost for a PT system. There are mainly 2 players in terms of cost:

- Operator costs:

- Infrastructure

- Vehicles and associated costs

- Workforce and fleet

- User costs:

- Time consumption

- Access

- Fee

In respect to PT design, both components have to be accounted for and be part of the design process.

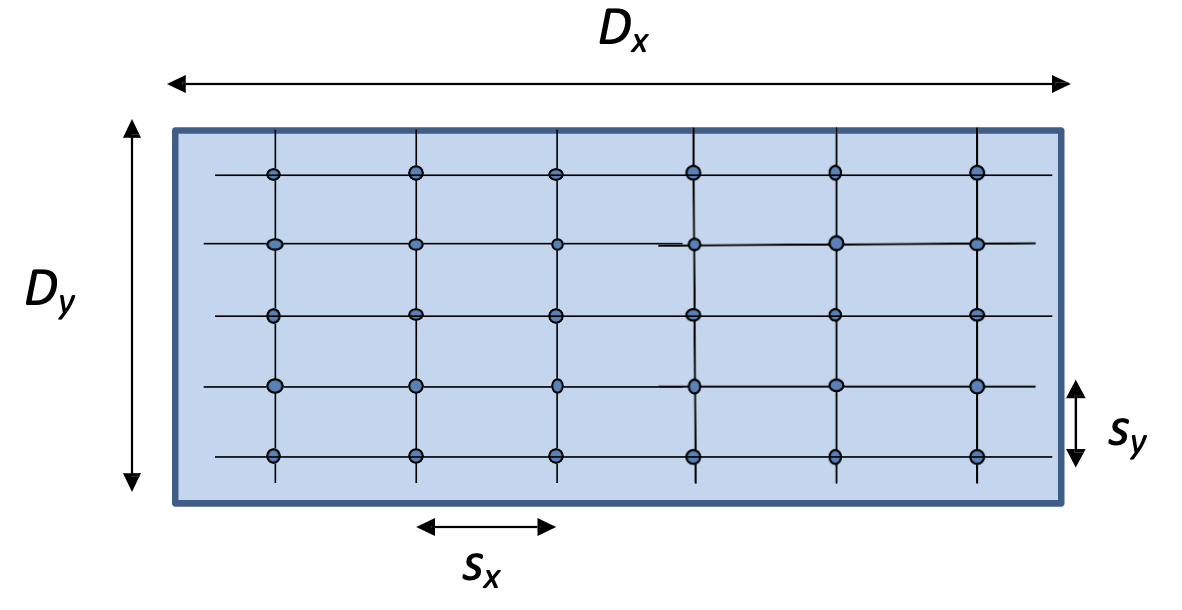

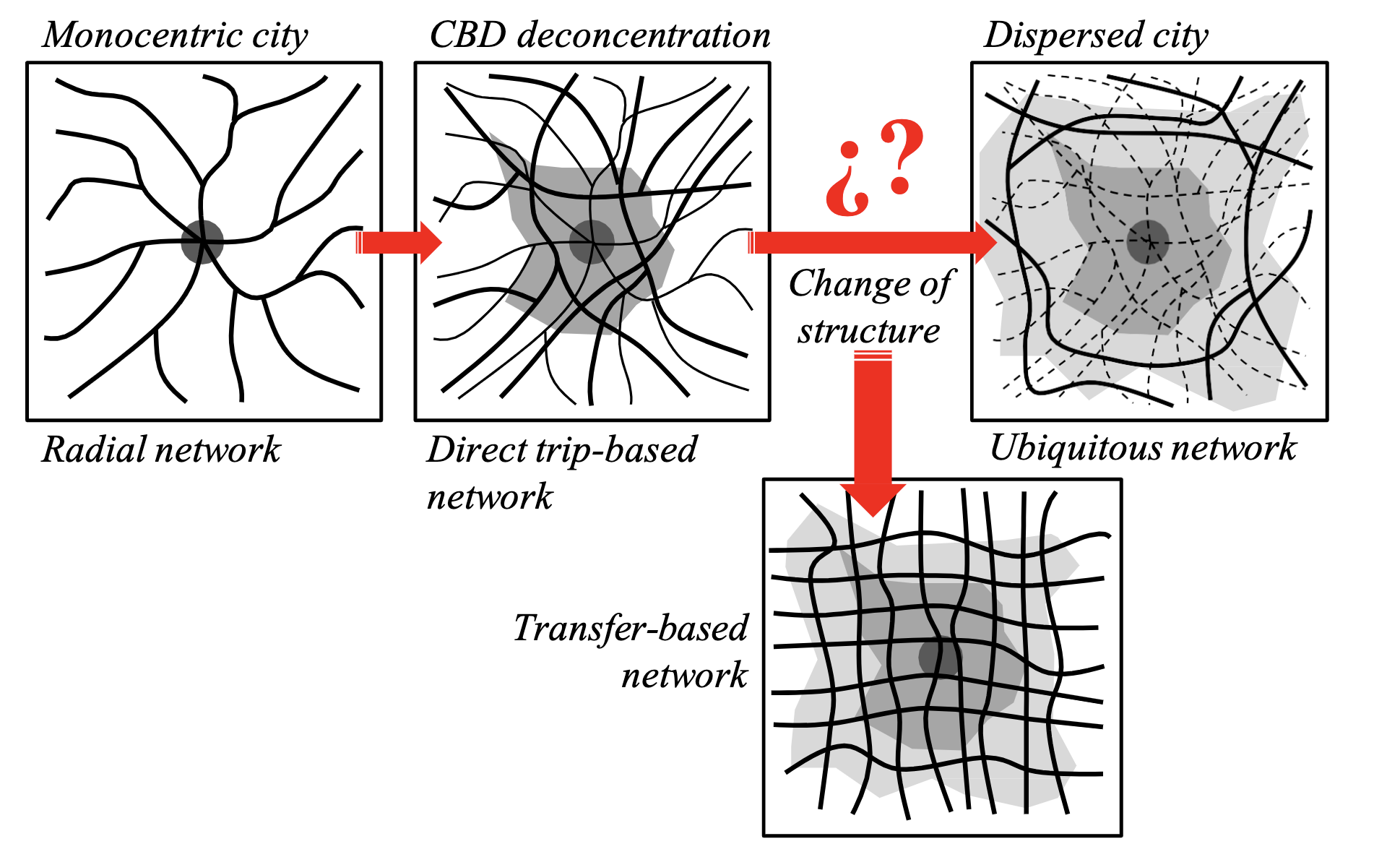

One of the most common approaches to network design is the Parsimonious models.

Network design approaches

When designing a PT network, different approaches can be followed.

One of the biggest difference is in having either a door-to-door line for every use case, or, on the contrary, basing the system on line transfers. They both have they're own advantages and disadvantages.

PT operations

Bus bunching

Bus bunching is a phenomenon in bus systems where 2 vehicles start running one right after the other, leaving a great gap somewhere else in the line.

The reason is the random passenger arrivals at the bus stops, since their individual boarding maneuvers delay the buses: if on arriving at a bus stop a bus finds more than the average number of passengers waiting, this bus will likely be delayed relative to the bus that precedes it. As a result the delayed bus may encounter more passengers on succeeding stops, and be delayed further. Further delays imply more passengers, which in turn imply more delay. This positive feedback mechanism is the reason[1]. But things are even worse... because as our bus falls behind schedule, it picks up passengers that should have been collected by the following bus. Thus, the following bus experiences less stopping delay so that it tends to catch up until the two buses eventually pair up and travel as a single unit. As time goes by pairs become bunches, until in the end there is a single moving unit. This is the bunching effect.

Read more about it at: http://faculty.ce.berkeley.edu/daganzo/Research/BusSim/index.html

Transit agencies often attempt to mitigate it by including extra time (slack) into their schedules, and then asking drivers to be punctual at selected control points along the route-even if this means delaying some buses. This method is of limited effectiveness because the slack has to be calculated by assuming a worst case scenario for the bus travel time between consecutive control points along the line, so that buses can stay on schedule despite disruptions. Worst case slack means slow travel times, which is not good for on board passengers-the medicine can be worse than the cure!

Today, as we can know the position of each bus real time, we can adopt real time strategies to avoid bus bunching.

More

Read more from slides